The back-story is here. The collection is here. You can subscribe over there. >>>

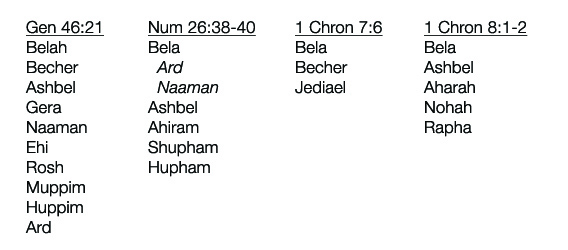

59. Who were the sons of Benjamin? Gen 46:21 vs. Num 26:38-40 vs. 1 Chron 7:6 vs. 1 Chron 8:1-2

Here’s what those verses get us:

(Ard and Naaman are in italics under Numbers 26 because they’re listed specifically as grandsons.)

I don’t think scripture really makes a point to tell us the entire, specific genealogy of Benjamin.

Chronicles

The NKJV ends 1 Chronicles 7:6 with the phrase “three in all,” but “in all” is in italics. Those italics indicate that the words were not part of the original text, but were added in order to make the text easier to understand for English readers. Sometimes these efforts are beneficial, and sometimes they are not. This may be a case of the later. Young’s Literal Translation renders that verse:

Of Benjamin: Bela, and Becher, and Jediael, three.

Does that mean there were only three, or that those three were the ones important to this genealogy? It can’t mean the former, if only a few verses later, at the beginning of the next chapter, five sons are recorded. Any author or copyist would have gone back and corrected the error.

Cultural Prefixes

Genesis 46 is listing the family that Jacob (aka Israel) took into Egypt. We’re told, in verses six and seven, that everyone went – sons, grandsons, etc. We’ve discussed previously that ancient Hebrew is not strict about assigning “grand-” or “great-grand-” prefixes to ancestors. Great-great-great-grandsons are simply listed as “sons” when heritage is the focus. Jesus is frequently called the “Son of David,” for example, because prophesy specifically stated that the Messiah would come from the line of David.

That Ard and Naaman are called “sons” in Genesis, and are listed as grandsons in Numbers, then, is no great surprise or contradiction. It’s cultural. It also indicates that some of the others listed as “sons” in Genesis may have been further down the line than first generation sons.

Names Change

We’ve also previously seen how frequently names are changed to reflect a person’s heritage or accomplishment, or when the culture they lived in changed. Benjamin’s family moved from a nomadic Hebrew culture into a pretty established pagan culture in Egypt. There were no birth certificates, no driver’s licenses. Names were descriptive and/or categorical, and changing them wasn’t entirely uncommon.

Timing and Purpose

Finally, the fact that Benjamin’s family is catalogued four separate times indicates that there are four reasons for the account. None of these books are parallels, like Kings and Chronicles – that give separate accounts of the same events. These are four chronologically separate histories that all list Benjamin’s family at different times or for different reasons.

Genesis tells us who went into Egypt with Jacob. The names listed in Numbers are due to a census, taken after Israel left Egypt hundreds of years later, and that the beginning of that chapter tells us was taken to count men 20 and older:

“Take a census of all the congregation of the children of Israel from twenty years old and above, by their fathers’ houses, all who are able to go to war in Israel” (Num 26:2).

Benjamin and the first few generations of his sons weren’t even alive when this census was taken, so these are obviously not the same “sons.”

1 Chronicles starts recording genealogy from Adam in chapter one, and continues that record in chapter after chapter. It’s no surprise that for such a long list of names, the author would only focus on the ones he was going to use again, or who may be remembered generations later, or who were simply the first.

Short answer: We’re not told. Because it’s not that important.